Studio Visit & Interview With Kelly Tunstall

Interview and Photographs by Brandon Joseph Baker

Kelly Tunstall’s surreal and whimsical paintings have captivated my interest since arriving in San Francisco from Kansas City two decades ago. It’s hard to pinpoint the first time I saw her fantastical figures or where, but I have a strong feeling it was at a show at 111 Minna Gallery. Which checks out after I dug into her lengthy CV with Hashimoto Gallery. Kelly is a well respected and prolific staple in the DNA of San Francisco’s art world. To be honest, I was a bit nervous to interview her at her studio but was excited to see the work she donated to Moth Belly’s Annual Auction and Fundraiser.

My fanboy nerves cast aside, I rode my motorcycle from Oakland to her studio in the avenues off California Street. Kelly greeted me at the door, offered me one of her last two beers and we sat down at her former dining room table which she repurposed to work side by side with her husband and partner in art, Ferris Plock. We talked as she picked a playlist revealing how she loves seeing live music, specifically she mentioned Thee Oh Sees (Osees), one of my favorites too. The common bond of shared music instantly transformed the studio visit and interview into a conversation about process, design, collaboration and family.

Kelly studied at California College of the Arts and Crafts in Oakland before the private college dropped ‘Crafts’ from the branding, repurposed the Oakland campus and consolidated curricula to San Francisco. Craft remains essential in Kelly’s work. As culture gravitates to a uniform, mass-produced and disposable digital environment, Kelly’s work indexes on the value of authenticity and adaptation. Her handmade moments weave private rituals and symbols from her everyday life as an artist, individual, mother and wife, into the conversation of her art. These conversations become literal creative banter in collaboration with Ferris as they sit next to each other working, frequently passing pieces back and forth.

“I’ve found resonance in the smaller details. When an idiosyncrasy connects with someone else, that is the most rewarding thing. If people want to share in the conversation, that’s great.” Kelly says of how her art continues to be a conversation with others long after the work leaves the studio for a gallery or a private collector.

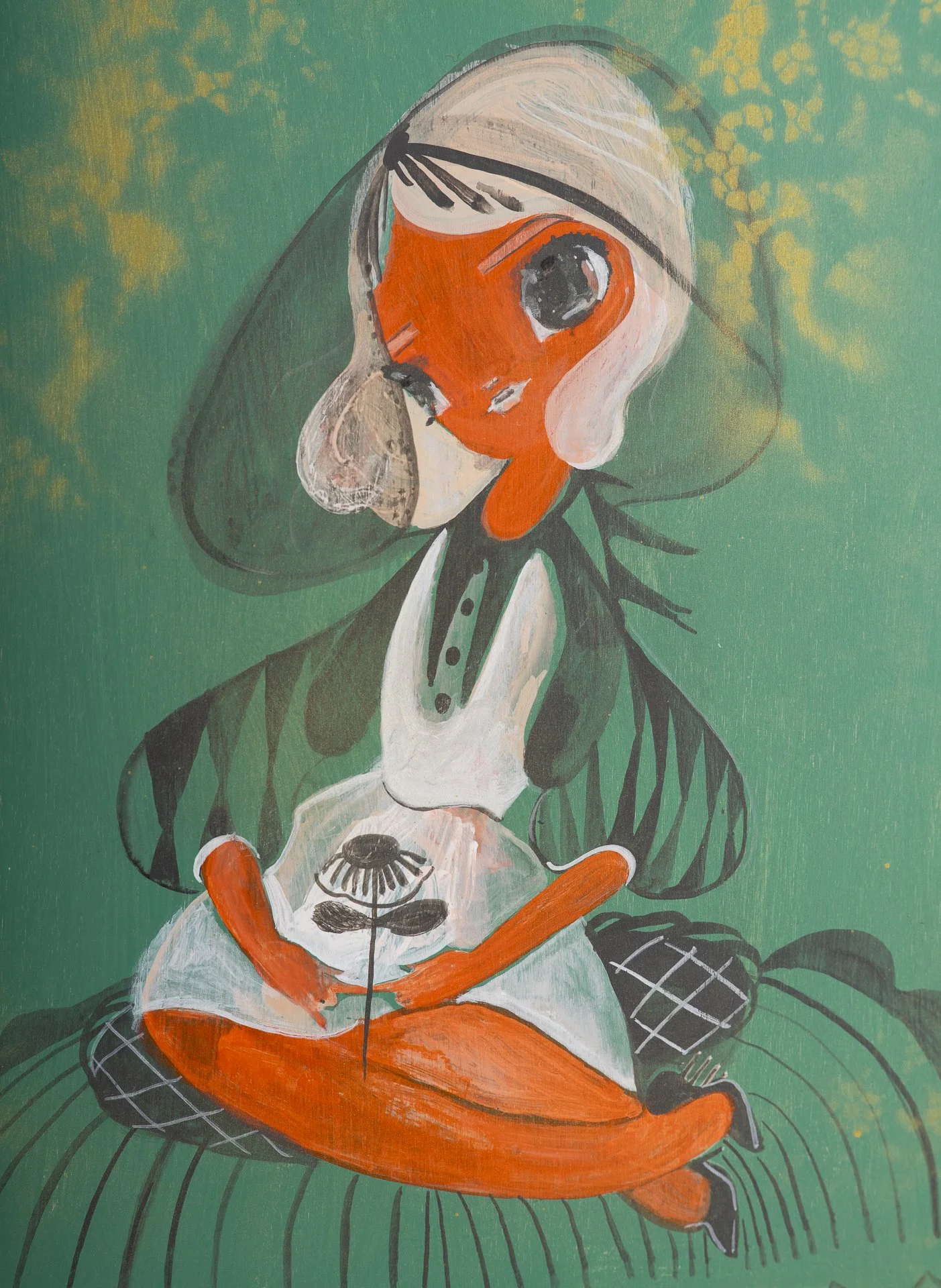

I find Kelly’s figures or portraits to be like underwater dreams; at once familiar and surreal. The figures are stylistically distorted; limbs bend fluidly while eyes are dilated, rounded and sit further to the side of the head than a human’s binocular vision. While our conversation meanders into sea anemones and how shrimp have adapted for survival, I wonder if it's possible - only while looking at her work, if my own eyes also become monocular like her portrait subjects. This fantastical brief daydream fits ubiquitously with the symbolic narratives Kelly weaves into her art. Kelly’s art provides space for imagination to manifest in a physical realm and to live out the everyday activities she finds so essential in life.

Interview

What motivates you to create or where do the ideas formulate that come to life in your studio work?

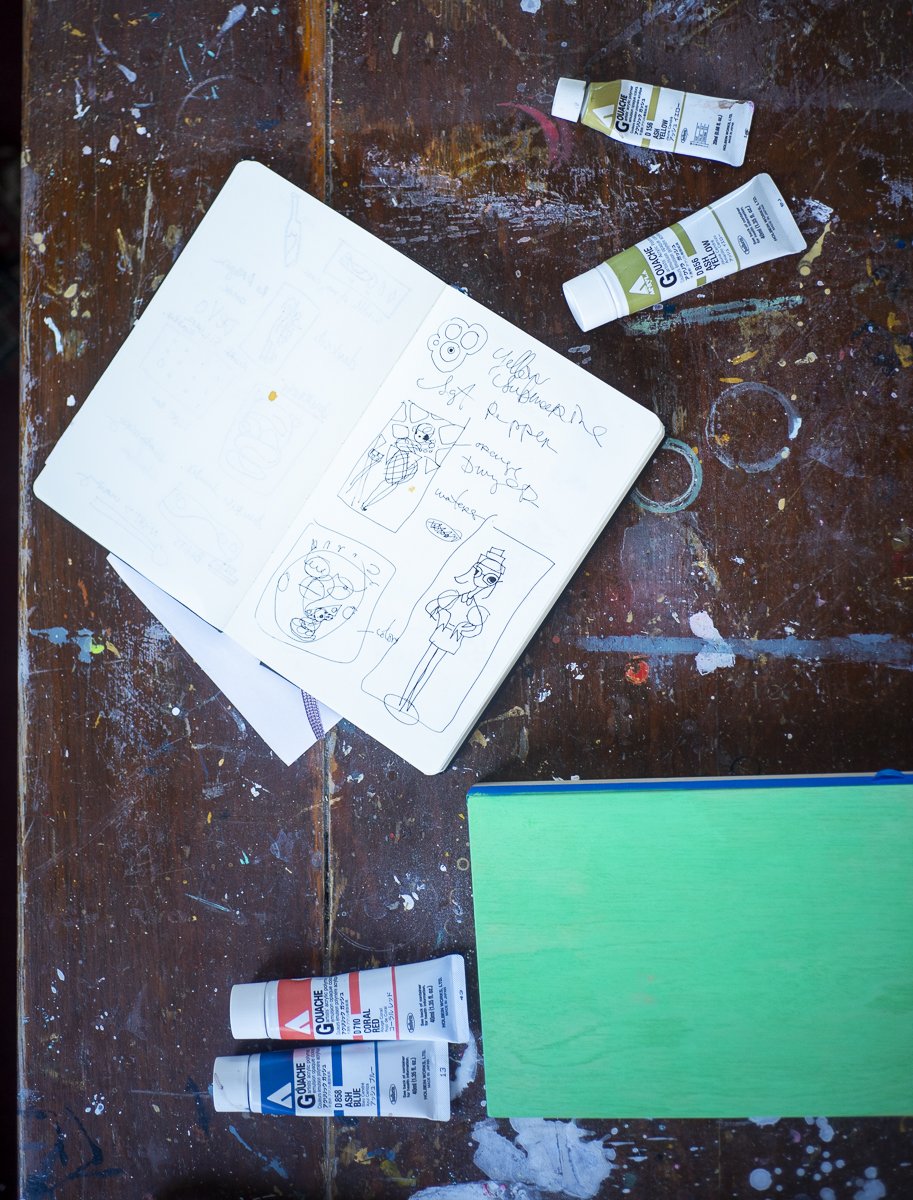

I like to work in my sketchbook, but I will kick the ball around in my mind and see what needs to add in, usually my subconscious will kick in a lot. Bigger ideas usually start there, and then I move directly to the panel. I get broad strokes down first and let the underpainting speak to me—there’s always something in the colors or the shapes that tells me where to go next. I’ll have a loose idea of composition and chalk it in, but I really let each piece evolve as I work. I’m not always trying to hit one specific image; the work finds its own path, and then I just keep adding details until it feels right.

I also really like visualizing and diagramming systems- the body (I love interior parts and processes), trees, electricity and sound. The characters can represent or be working within those systems, sometimes there is a basis in reality, and sometimes I’ve made up my own versions. Those can be the foundations for the works, so the characters can be working in or on them, hanging out near them or have become the systems themselves.

You share your studio with Ferris Plock, your husband and creative partner in life and art. Can you describe how you two collaborate on work?

After so many years, the way we work together is very fluid. Most pieces start as a conversation—sometimes we can decide the concept of an entire show easier than deciding what’s for dinner. When an idea clicks, we both feel it. We each bring our own layers, and the collaboration is real in every sense. Whatever is happening in our personal lives, or in the city around us, moves into the work. It’s not exactly a diary, but it definitely carries both of our perspectives.

We talked about how you hide private rituals, personal moments, and universal truths in your work and celebrate them as symbols in your art. For me the piece in your hallway, Cost (Price of Milk) is a great example of a relatable personal moment turned fantastical. Can you tell our readers more about it—and why those moments matter to you?

Cost (Price of Milk) is a very real ode to needing milk for the morning after a night out—knowing that if there’s no milk for everyone the next day, it’s a disaster. So there I was, heading home in an amazing outfit, stopping at the Safeway in the Castro at 2:30 a.m. It is a human moment- one of my favorite ways to play in my work (I’m always playing, or working something out), through elevating really real, maybe simple things. Gotta have milk for cereal and coffee, though. The world stops for no one and nothing.

Glamorous truths elegantly wrapped in systems or processes. It might make sense to only me, but that’s art for you.

That said, I cherish living in San Francisco each and every day.

One CAN get milk in the middle of the night and there’s lots of folks doing the same thing, or some THING is going on.

I enjoy being a part of the fabric of this city. One little tiny piece, a small participant, but a respectful loving observer always too.

….There’s a chow fun delivery tied somewhere on the handle of a restaurant, but the car alarm birds have quieted since cars don’t really do that siren thing anymore…. The details get me.

These things go into the notebook, where I have paid respect to it, and I feed it back into the system and maybe it makes it into a painting.

The figures in your work have a distorted perspective—elongated limbs and features—which I really enjoy. Is there a symbolic meaning behind the distortion or something you’re intentionally trying to communicate to the viewer?

It started as a way to see how far I could push things- a little game. I can draw realistically, but tricks of the eye and mind are interesting to me. The stretching, the extra hands or feet—it’s part composition, part surreal logic, and I take the joy in bending reality or questioning it, poking holes in it, or organizing it differently than perhaps one might expect, even if it’s subtle.

I love giving the characters something extra to work with, some twist on the truth. One of the first times I exaggerated a figure was painting my mom; she has a long neck and used to be self-conscious about it, so I elongated it even more to celebrate it. She still has that piece, painted on floral curtain blinds. Portraiture is full of tricks; I just lean into it a little more than some, exploiting the uncanny valley a bit.

Can you tell me a little more about the eyes in your work? They appear to have multiple reflections like there are many light sources. What are your thoughts behind how you paint the eyes, and how did you develop that style?

The eyes - windows and mirrors - amazing.

The eyes let you shift the focus quickly—as humans, it’s where we’re programmed to look first- therefore they’re directional cues and compositional anchors.

I also typically consider how light might reflect in the eyes in the space where the piece will live, or things in its immediate painted environment. Around 2004, I heard about deep-sea shrimp with extra eye cones and imagined: what if my girls had extra irises? Maybe they could see differently, or more clearly, or WHAT EXACTLY IS OUT THERE?

I love the mystery of that idea. I think a lot about science and survival when I’m working—how these characters might adapt or thrive in their world. They’ve become a kind of family of misfits with secret powers, though that’s mostly my inner narrative. If someone simply sees them as beautiful portraits, that’s totally fine.

What is your take on the DIY art community in San Francisco and how has that changed from when you first moved here in 1998?

The most important part of the DIY scene has always been community—showing up for each other. When I first moved here, there was just something going on all the time, like literally always.

Studios were more affordable, it was dirty and we got weird but everything and everyone felt supported. You could scrounge something up from somewhere, and likely someone would pour you a free beer along the way. I painted in the basement of 111 Minna Gallery for a while, and sometimes on the floor when I was working on shows- the light was so pretty. I owe the very beginning of my work in San Francisco to their support. The skate warehouses are still here, so that’s good. I like that.

People took care of one another, I know it’s the same on some level. I’m encouraged by how those energies are reinventing themselves.

I feel the resurgence in spaces like Moth Belly.

Moth Belly Gallery during an opening reception in 2025

I wish I could see more of it, since 1998, life changed a bit, we got a little quieter (not for lack of enthusiasm of all of the above), maybe a little more private, and our involvement is adapting to places that we have the visibility to respond in meaningful ways- right now this means a lot of different things.

Our family has been very involved in Hospitality House on an ongoing basis: there is now a permanent home for the Community Art Program, where anyone can do work on art for free at 6th and Market. The boys attend SFUSD schools (public schools), and now I am VP of Ruth Asawa School of the Arts PTSA, so it’s really feeling great to see the next generation in the mix too, and find ways to continue good things and support the next creatives as we can.

Art is not everything, I know, but it can be the start of someone’s story as it was mine.

What can we expect to see from you at your next show?

The next show is called Music Island. It’s a place you go when you’re immersed in music—listening, performing, drifting. It’s coming from a place of respect and also a profound curiosity.

We’re thinking about the rituals around music, even the invisible ones, and playing with symbology, sound systems, and magic. Some pieces come from personal stories, others from more universal experiences, and we’re letting them all hang out together.

It’s really an earnest meditation on the joy and weirdness of being a part of an ecosystem, so you’ll be experiencing some real time processing and diagramming of functions in this body of work, where we have reordered or rewired some mental maps along the way too.

It’s been fun to work through, though it was really intimidating at first (music is actually everything), we have reached a conclusive space that I think works.

Kelly Tunstall’s work “Morning/Mourning” is featured in Moth Belly Gallery’s 6th Annual Auction and Fundraiser and can be seen at the gallery or purchased through November 29th, 2025.